Let me shed some light on a concept that is dear to my heart: Urban wineries are challenging the established idea of terroir. They form a completely different aspect to it: with wine that is crafted and produced in the hustle and bustle of a city, usually quite a drive away from the location where the grapes are grown but influenced by a fast-paced and cosmopolitan surrounding.

Almost everyone I spoke to who works in an urban winery told me that they love city life – they would actually not see themselves settling in a rural and quiet environment. At the same time they are passionate about creating a beautiful product from fruit grown in nature and that strongly expresses its origin. This origin usually isn’t urban but very rural – a vineyard with plants, insects, trees, and other animals living in harmony and peace, rather than traffic, supermarkets and restaurants around them.

When deciding on an urban winery location, space, power and water, sewer/water discharge and proximity to wine aficionados are the main criteria – but of course also cost and access to grapes.

I had always asked myself if and how such combination would be possible. I really wanted to be involved in wine making, but I just do not see myself in a remote and beautiful landscape without the buzz of cafes, restaurants and public transport.

My first aha-moment happened when I went to an urban winery in 2013 without even knowing what it was: Macy Gray gave a super small unplugged show at City Winery in Manhattan. I had bought tickets as I thought it would be super cool to go to an intimate concert while visiting New York. When I went downstairs to the bathroom at the location,

I was puzzled about the barrels that were stocked up on the way.

By the following trip to New York in 2017, I had started to develop an interest for wine and wanted to understand more. I then had Brooklyn Winery on my list and had actually booked a visit: A beautiful bistrot, wine bar, and proper winemaking area with lots of equipment, tanks, open fermenters – actually with grapes in them at the time. It was early November and the reds were still on skins, being punched down twice per day. The winemaking area was separated from the restaurant with a glass wall. The visit I did back then was stunning. I took a bottle of their Riesling home with me that had its bottle number (205) written on the label. So personable. The grapes had been sourced from the Finger Lakes region, only a couple of hours away from the winery. During the visit, the staff explained that some fruit even comes all the way from California and travels in a cooled truck for a full day. I was amazed that someone actually took the effort to create a space for winemaking right in Williamsburg and transported the grapes across such long distances, to make wine between second-hand shops and small cute bakeries and cheese stores.

And it turned out that the assistant winemaker, Luigi, who worked there at the time, and who I later spotted on my pictures, and I met again in Franciacorta, Italy, about 8 years later.

A short fact about Brooklyn winery’s upscaling over the following years: their winemaking grows and changes from vintage to vintage. In 2019, they produced 84 tons of wine and with that, over 64,000 bottles – a proper medium size winery. At the same time, a main part of their business concept was around the winery as an event space- for weddings, wine events and business bookings. Now, in 2025, they are pulling it all back to the roots: wine tastings and educational events with a limited wine bar menu are now back at the core of their business.

In 2018, I visited London Cru in a London backyard for a Winemaker for a Day event. It was fascinating how you could craft your own blend with grapes that don’t always grow together in one zone. London Cru put a focus on importing healthy and well-cared for fruit from Italy and Germany.

Some months later I met my now close friends Amy and Jasper whose Downtown Los Angeles winery I crowdfunded. They had offered some supporters to help them harvest grapes and I signed up for it immediately. A beautiful friendship across continents developed.

Also later that year, I stumbled upon Dorrance Wine in Capetown for a more or less accidental tour and a stunning multi-course menu for New Year’s Eve. The wines that came with it were all produced onsite and fabulous expressions of South African winemaking.

I love cities and I love wineries – so whenever I can, I hunt for the combination: La Tetue in Lyon (which heartbreakingly just ended its operations), Renegade in East London, The Winery Hotel in Stockholm, Wijnfaktorij in Antwerp, Gudule in Brussels, La Micro Winery in Bordeaux, Imi in Cologne, Oddio Bowden in Adelaide, Chai Uva in Sete, Dormilona in Margaret River, Cantina Urbana in Milano and Donkey & Goat, Hammerling Wines and Broc around Gilman Wine Block in Berkeley. And some more are on the list of places I really want to visit.

Those urban wineries have some things in common that set them apart from other wineries:

- The owners didn’t take over the winery from their parents, so they made winemaking their individual choice. Jon of IMI Winery in Cologne actually did inherit some vineyards, but no winery with it, and he decided to settle down with Svenja a 3 hour drive away from the vineyards in the German Pfalz, in Cologne.

- Some of them have a second job to secure their income. Winemaking – especially in cities where cost for rent, labor and transportation is expensive- can be a very romantic idea that needs high investment and that provides insecure income.

- Urban winemakers leverage the benefit of being close to customers and create community.

Most of those urban wineries host events and collaborations with other local businesses, from restaurants to food trucks to breweries. They connect with their customers and let them connect with each other, and by this, form a sense of belonging. The Berkeley wineries around Gilman block do First Fridays – basically street festivals along the whole block that is occupied by several wineries specialized in sparkling, organic and natural wines.

- They create magnetism to draw people to the winery and get their sales going: They create programs to stay in touch with their customers and create a sense of community: with wine club memberships that give customers the chance of exclusive events and releases of new and special wines, but also give the winery a monthly income guarantee as the club member buys a specific amount of bottles on a subscription-basis.

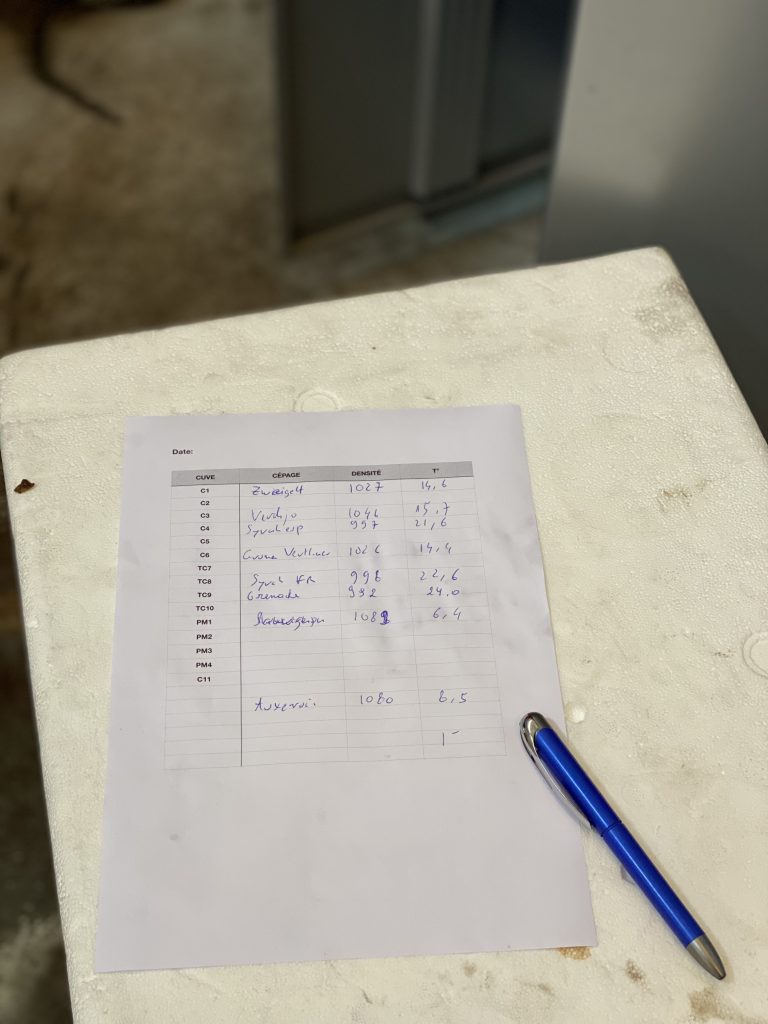

- While being distant from the vineyard, who manages an urban winery is still very alert for the stage of ripeness of their grapes. Often the winemaker needs to rely on someone else’s assessment of the perfect harvest date. And they might change plans and shuffle logistics around on short notice when they check the weather, receive an excited phone call or get to the vineyard for a quick check.

- Those who do not have their own vineyards have a lot of flexibility and can work with a variety of quality and origin of grapes. Like Thierry of Gudule, the winery in Brussels, gets grapes from various countries around Belgium: from France, to Germany, Italy and Austria. Blending the varieties, he makes cuvees that you would never get anywhere else.

- Crowdfunding is a well-accepted option to cover investments to build or expand the winery (both Angeleno and Imi Winery initiated crowdfunding successfully and I actually met them through that) – and it’s an impactful way of communicating even before the business kicks off.

- Winemakers in cities ask for help a lot: friends, family and also regular customers assist them with almost all winemaking steps: from harvesting grapes, to processing them, to bottling, labelling, and tasting new vintages.

- Some of them, like Imi and Vallee du Venom, have an additional small shop to sell their wines, some other small local specialties and for tasting. It’s to attract those customers who are not aware of their existence or just don’t make their way to the sometimes secluded location.

- The architecture of an urban winery is typically less “chateau-style” than a stereotype winery as you know it from Bordeaux, South Africa or Burgundy. Sometimes the buildings are rugged, rather industrial, hidden in a backyard or behind a large metal door, and easily overseen. Yet, customers seem to not miss the rural winery architecture and appreciate the diversity of locations around it when they commit to an urban winery. Geraldine of La Tetue rents an old Vespa workshop for her winemaking in the city center of Lyon. Dorrance in Capetown have a designated winemaking space behind their restaurant. Steve from Oddio Bowden occupies a building in an industrial space that was previously a church, and he offers the space as a custom-crush location. And La Micro Winery shares a huge industrial space with a chocolate production, bakery, pizza bistro and associations for social services in Bordeaux.

La Micro Winerie, Bordeaux

Patrick at Wijnfaktorij in Antwerp even provides the opportunity of window shopping – his winery is in the heart of the shopping area of the old town. Yet, the space is perfectly designed for the production of approx. 7000 bottles per year, with grapes from his own vineyards within 1 hour driving distance. He avoids using pumps or filters, and moves his wine mostly by gravity. His winery is a shop, tasting room and full-on production space altogether.

Wijnfaktorij’s vineyard, Antwerp

Wijnfaktorij, Antwerp

Those urban wineries with a big enough production offer educational events. And in some cases customers can actually get involved in the winemaking process themselves: The Winery Hotel, in the outskirts of Stockholm, is taking it to the next level: You can sit in the hotel lobby and watch the enologist during their work. Or you book a tour to be shown how all steps of the winemaking are done, or you get yourself a tasting flight out of the cooled self-serve machine.

Angeleno Wine in LA let their wine club members harvest and stomp grapes at the end of a long harvest day. They get a glass of wine with it and they love it.

London Cru offers their Winemaker for a Day event that gives customers the opportunity to learn about how wine is being made, where the grapes come from, but also how blends are being crafted at the end of the winemaking process. And they can blend their individual small bottle of wine from different batches, and then take it home with them.

This provides a unique insight into not only the product but also into how it’s made, without having to travel to a vineyard.

A study published by University of Stellenbosch also shows the profile of an urban wine consumer: those who chose urban wineries over other types of wineries tend to consider wine as an important part of their lives. Yet, they say about themselves that they possess rather low levels of wine knowledge: “new to wine” or “basic knowledge” is what they account for themselves. At the same time, they are likely to belong to one or more wine-related community organization (e.g. wine clubs). Interestingly, while they consume the higher number of bottles per month compared to other customers, the frequency of their wine consumption is lower. In a nutshell, the findings show that urban wineries are preferred by consumers with higher involvement but lower knowledge – and with that, they offer a wide range of educational and experience-focused activities around the winery that gives them the chance to learn about enology without leaving the urban environment.

Urban wineries bring about new aspects to terroir

Looking at all the mentioned aspects, one might redefine terroir in the context of wine that is made in a city. Various factors influence the winemaking and its consumption in this context, and bring about a vibrant yet fragile approach to producing wine where it’s drunk most.

Culture: A perspective on terroir that defines winemaking as a cultural ecosystem, shaped by the people who grow grapes and those who make wine, the traditions they bring, their agricultural and enological practices merging with the vibrancy of an urban environment inspiring each other.

Sustainability: With environmental and economic concerns, as well as resource scarcity, sustainability is becoming a fundamental element of making wine. Urban wineries are often located in repurposed buildings, turning old warehouses or Vespa workshops into production spaces and adaptively reusing them.

Sustainable practices like conscious water and waste management, reducing resource intake and circular approaches are being discovered, also to manage the high cost of maintaining an urban winery. Possibilities for this in cities are huge and different from those in rural areas.

Innovation: Urban wineries often blend old-world traditions with modern or innovative techniques. Space-optimized set-ups and work processes, shared production sites and unconventional packaging and logistics let winemakers sell in bulk with kegs for restaurants, for example. Or they limit their logistical risk when they, for example, deliver locally like Géraldine in Lyon used to, taking bottles to her customers by bike, and providing customers the opportunity to return the bottles to her winery so she could reuse them.

Community: The experience of wine isn’t just about taste, but also about the social context in which it’s consumed. Urban wineries create community where people can connect with the culture of winemaking and with each other, learn from producers, attend tastings, and become part of the process – if they like on a regular basis even.

All these aspects of terroir become a distinct part of the urban winery’s identity, even if far away from soil, climate and ecosystem of where the grapes are grown.

Urban wine terroir is also about connection — to the land, to the maker, to traditions and innovations, to the surrounding and the community.

For me personally, the main magnetism of any urban winery goes beyond their business model, logistics, rent and permits, varieties and origin of the grapes: my admiration goes to the people who have the courage and inspiration to drive winemaking and love the city just like me.

Sources:

Natalia Velikova, Texas Tech University, USA; Phatima Mamardashvili, International School of Economics at Tbilisi State University, Georgia; Tim H. Dodd, Texas Tech University, USA; Matthew Bauman, Texas Tech University, USA (2019); Selling wine in downtown: Who is the urban winery consumer?, Proceedings of the 11th Conference of the Academy of Wine Business Research (AWBR); University of Stellenbosch, Editors: Nic S Terblanche & CD Pentz; competitive papers, retrieved from https://researchmgt.monash.edu/ws/portalfiles/portal/281674736/FINAL_PROCEEDINGS_11th_AWBR_CONFERENCE.pdf on April 7, 2025

Barber, N. A., Donovan, J. R., & Dodd, T. H. (2008). Differences in tourism marketing strategies between wineries based on size or location. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 25(1), 43-57.

Bell, S. J. (1999). Image and consumer attraction to intra-urban retail areas: An environmental psychology approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 6(2), 67-78.

Lalli, M. (1992). Urban-related identity: Theory, measurement, and empirical findings. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12(4), 285-303.

McKinsey, J. (2008, March). Making wine in the city. Wine Business Monthly. Retrieved from https://www.winebusiness.com/wbm/index.cfm?go=getArticle&dataId=54607

McMillan, R. (2017). Is opening a downtown tasting room smart? Retrieved from http://svbwine.blogspot.com/2017/09/is-opening-downtown-tasting-room-smart.html

Weinberg, B. (2011, April 4). How urban wineries succeed. Wines & Vines. Retrieved from https://www.winesandvines.com/news/article/85840/How-Urban-Wineries-Succeed

McKinsey, John A. (2008, March 15). Making Wine in the City. The business and regulation of the urban winery. Retrieved from https://www.winebusiness.com/wbm/article/54607